Inside the psychology of lawyer burnout with Dr Catherine Sykes: why some burn out and others don't

The early signs lawyers miss and why burnout is often mistaken for productivity.

Contents

Burnout has become a familiar theme in legal careers, but it remains poorly understood. Long hours and competitive environments are often treated as the main drivers, while far less attention is paid to the psychology that determines who burns out and who doesn’t.

That gap is where London-based psychologist Dr Catherine Sykes has spent much of her career. After starting out in academia researching the psychological factors that protect against burnout, she moved into private practice and gradually found herself working primarily with lawyers.

Nearly two decades on, her work focuses on how pressure, performance and personal identity intersect in the profession.

Stay ahead of the City law market with our free email briefing - essential industry news and analysis, in your inbox three times a week.

How it began

Sykes did not set out to work with lawyers. She started in academia, researching burnout among carers for people with Alzheimer’s disease, a group widely assumed to be at exceptionally high risk for burnout.

What she found challenged some of the prevailing assumptions about burnout.

Burnout, she explains, was not most strongly linked to how demanding the care itself was, or even to the level of disability involved. Instead, it was psychological variables - the way people related to pressure, responsibility and rest - that determined whether someone burned out or not.

After having her first child, Sykes decided to leave academia and gradually transition into private practice. She began slowly, opening a City office one day a week and offering what she knew best: burnout support.

“It just so happens that the majority of people that came through my door were lawyers and that was 17 years ago,” she says.

She eventually left academia altogether and built a full-time practice, expanding into coaching and services tailored specifically to lawyers.

What causes burnout for lawyers

There is no single cause of burnout, Sykes says. Instead, it emerges from a combination of individual traits and organisational conditions, a combination that appears frequently in legal environments.

“The environment of practising lawyers is highly competitive so naturally there’s going to be a lot of stress, but it’s also the expectations people put on themselves.”

Layered on top of that is a lack of control over time and workload. “Many lawyers don’t feel a sense of agency, they don’t feel in charge of their day or their workloads. When you pair stressful environments with high demand from clients, high demand on the self, low value of rest, low sense of agency…”

Perfectionism then completes the picture. “There is a fixed mindset that often comes along too. There’s this expectation to be perfect all the time and that your perfectionism needs to be effortless,” she says.

Over time, this can create friction. “This can create a disconnect between the body and the mind and people don’t notice those early warning signs or dismiss them as a sign of weakness - ‘I shouldn’t be feeling like this’ or ‘I used to be able to do all these things’.”

Early warning signs people miss

Burnout rarely arrives suddenly, even if it feels that way in hindsight. Sykes says the earliest signs are often subtle and easily rationalised away. The biggest red flag, she says, is irritability.

“If your energy is spent largely on work, you’re going to get irritated when people want something from you. Irritability with colleagues, with people at home - it’s a big sign that you’re on the track to burnout,” she says.

Another is a loss of motivation. “Everything feels a bit the same, like you’re dragging your heels a little bit, waking up and not feeling energised, like you could do with another night’s sleep.”

Irritability with colleagues, with people at home - it’s a big sign that you’re on the track to burnout.

At this stage, people often respond by doing more, not less. “If you’re burnt out, you’re doing too much of the wrong things. There’s often a fear of failure so people don’t challenge themselves, don’t grow and then become very stuck in doing more of the same, rather than something new and challenging,” she says.

That stagnation is particularly damaging for high performers. “We need challenges to feel alive, especially high performers. If you’re not reaching your potential because of fear of failure, you often get this misaligned feeling that you’re not giving as much as you could.”

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addleshaw Goddard | £52,000 | £56,000 | £100,000 |

| Akin | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Baker McKenzie | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| Bird & Bird | £48,500 | £53,500 | £102,000 |

| Bristows | £48,000 | £52,000 | £95,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Burges Salmon | £49,500 | £51,500 | £76,000 |

| Charles Russell Speechlys | £52,000 | £55,000 | £93,000 |

| Cleary Gottlieb | £62,500 | £67,500 | £164,500 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clyde & Co | £48,500 | £51,000 | £85,000 |

| CMS | £50,000 | £55,000 | £120,000 |

| Cooley | £55,000 | £60,000 | £157,000 |

| Davis Polk | £65,000 | £70,000 | £180,000 |

| Debevoise | £55,000 | £60,000 | £173,000 |

| Dechert | £55,000 | £61,000 | £165,000 |

| Dentons | £52,000 | £56,000 | £104,000 |

| DLA Piper | £52,000 | £57,000 | £130,000 |

| Eversheds Sutherland | £50,000 | £55,000 | £110,000 |

| Farrer & Co | £47,000 | £49,000 | £88,000 |

| Fieldfisher | £48,500 | £52,000 | £100,000 |

| Freshfields | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Fried Frank | £55,000 | £60,000 | £175,000 |

| Gibson Dunn | £60,000 | £65,000 | £180,000 |

| Goodwin Procter | £55,000 | £60,000 | £175,000 |

| Gowling WLG | £48,500 | £53,500 | £105,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| HFW | £50,000 | £54,000 | £103,500 |

| Hill Dickinson | £43,000 | £45,000 | £80,000 |

| Hogan Lovells | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Irwin Mitchell | £43,500 | £45,500 | £78,000 |

| Jones Day | £60,000 | £68,000 | £165,000 |

| K&L Gates | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Kennedys | £43,000 | £46,000 | £85,000 |

| King & Spalding | £62,000 | £67,000 | £175,000 |

| Kirkland & Ellis | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| Latham & Watkins | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Mayer Brown | £55,000 | £60,000 | £150,000 |

| McDermott Will & Schulte | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Milbank | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Mills & Reeve | £45,000 | £47,000 | £84,000 |

| Mischon de Reya | £50,000 | £55,000 | £100,000 |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | £56,000 | £61,000 | £135,000 |

| Orrick | £60,000 | £65,000 | £160,000 |

| Osborne Clarke | £55,500 | £57,500 | £97,000 |

| Paul Hastings | £60,000 | £68,000 | £173,000 |

| Paul Weiss | £60,000 | £65,000 | £180,000 |

| Penningtons Manches Cooper | £48,000 | £50,000 | £83,000 |

| Pinsent Masons | £52,000 | £57,000 | £105,000 |

| Quinn Emanuel | n/a | n/a | £180,000 |

| Reed Smith | £53,000 | £58,000 | £125,000 |

| Ropes & Gray | £60,000 | £65,000 | £165,000 |

| RPC | £48,000 | £52,000 | £95,000 |

| Shoosmiths | £45,000 | £47,000 | £105,000 |

| Sidley Austin | £60,000 | £65,000 | £175,000 |

| Simmons & Simmons | £54,000 | £59,000 | £120,000 |

| Simpson Thacher | n/a | n/a | £178,000 |

| Skadden | £58,000 | £63,000 | £177,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Squire Patton Boggs | £50,000 | £55,000 | £110,000 |

| Stephenson Harwood | £50,000 | £55,000 | £105,000 |

| Sullivan & Cromwell | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Taylor Wessing | £52,000 | £57,000 | £115,000 |

| TLT | £44,000 | £47,500 | £85,000 |

| Travers Smith | £55,000 | £60,000 | £130,000 |

| Trowers & Hamlins | £47,000 | £51,000 | £85,000 |

| Vinson & Elkins | £60,000 | £65,000 | £173,077 |

| Watson Farley & Williams | £51,500 | £56,000 | £107,000 |

| Weightmans | £36,000 | £38,000 | £70,000 |

| Weil | £60,000 | £65,000 | £170,000 |

| White & Case | £62,000 | £67,000 | £175,000 |

| Willkie Farr & Gallagher | £60,000 | £65,000 | £170,000 |

| Withers | £47,000 | £52,000 | £95,000 |

| Womble Bond Dickinson | £43,000 | £45,000 | £83,000 |

Rank | Law Firm | Revenue | Profit per Equity Partner (PEP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DLA Piper* | £3,130,000,000 | £2,500,000 |

| 2 | A&O Shearman | £2,900,000,000 | £2,000,000 |

| 3 | Clifford Chance | £2,400,000,000 | £2,100,000 |

| 4 | Hogan Lovells | £2,320,000,000 | £2,400,000 |

| 5 | Linklaters | £2,320,000,000 | £2,200,000 |

| 6 | Freshfields | £2,250,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 7 | CMS** | £1,800,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 8 | Norton Rose Fulbright* | £1,800,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 9 | HSF Kramer | £1,360,000,000 | £1,400,000 |

| 10 | Ashurst | £1,030,000,000 | £1,390,000 |

| 11 | Clyde & Co | £854,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 12 | Eversheds Sutherland | £769,000,000 | £1,400,000 |

| 13 | Pinsent Masons | £680,000,000 | £790,000 |

| 14 | Slaughter and May*** | £650,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 15 | BCLP* | £640,000,000 | £790,000 |

| 16 | Simmons & Simmons | £615,000,000 | £1,120,000 |

| 17 | Bird & Bird** | £580,000,000 | £720,000 |

| 18 | Addleshaw Goddard | £550,000,000 | £1,000,000 |

| 19 | Taylor Wessing | £526,000,000 | £1,100,000 |

| 20 | Osborne Clarke** | £476,000,000 | £800,000 |

| 21 | DWF | £466,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 22 | Womble Bond Dickinson | £450,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 23 | Kennedys | £428,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 24 | Fieldfisher | £385,000,000 | £1,000,000 |

| 25 | Macfarlanes | £371,000,000 | £3,100,000 |

What do City lawyers actually do each day?

For a closer look at the day-to-day of some of the most common types of lawyers working in corporate law firms, explore our lawyer job profiles:

Burnout versus productivity

Burnout often masquerades as productivity, fuelled by adrenaline rather than alignment, particularly in environments that reward long hours and being seen as busy.

“At first, it can feel quite good, quite uplifting, but it’s just adrenaline,” she says.

“There’s a difference between feeling good because you’re running on adrenaline and feeling good because you’re aligned - your mind, body, relationships, work, your impact.”

Rest comes first

One of the biggest mistakes people make when they realise they are burnt out is trying to make big decisions too quickly.

“The first thing is rest. Don’t make any decisions when you’re burnt out,” she says.

“If you don’t address what you are bringing to that burnout, you might get another job and just repeat the same patterns.”

That advice often runs up against deeply ingrained beliefs some people hold about rest.

“There’s a mentality of it’s a bit embarrassing to take care of yourself. If you have to take care of yourself, maybe you’re not as strong as you think you are. It’s a badge of honour to be someone who does need rest, who can operate on only a small number of hours of sleep.”

There’s a mentality of it’s a bit embarrassing to take care of yourself.

Rest itself, she notes, is not straightforward when someone is already burnt out.

“When you’re in a burnout state, rest is difficult physiologically because you are hyper-alert and it’s hard to transition into a rest state, which is why pacing is important.”

Sykes recommends building routines that include intentional rest. She says performance improves when periods of intense, cognitively demanding work are followed by lighter tasks, such as emails, before a short rest. That gradual step-down in intensity also makes it easier to enter a genuine state of rest.

Impostor syndrome (at every level)

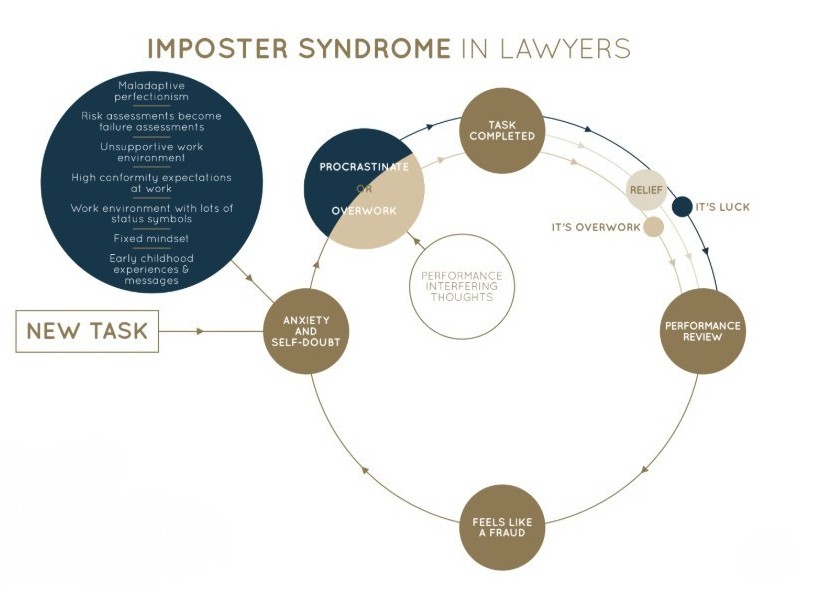

Alongside burnout, Sykes also sees another closely linked pattern. Impostor syndrome, she says, is deeply misunderstood, including by those who experience it.

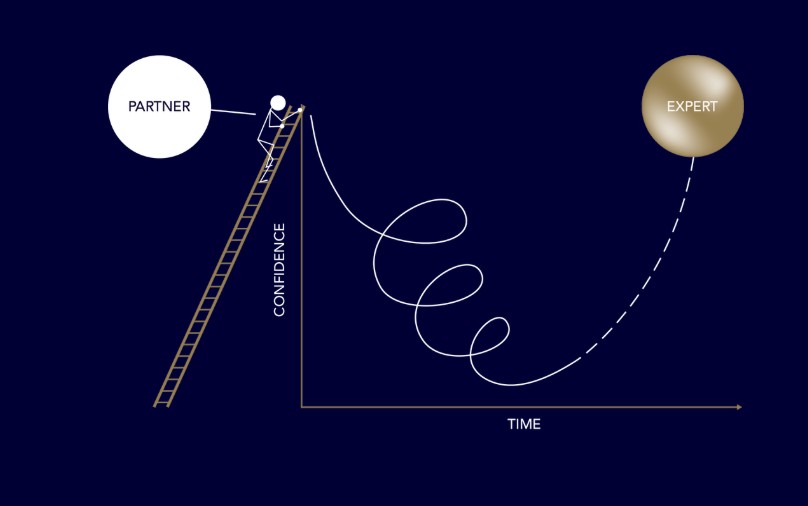

It tends to surface at transition points: the start of a career, moments of growth, or taking on new responsibilities.

When you’ve made partner, that’s when impostor syndrome creeps right back in because it’s a new challenge.

“When you’ve made partner, that’s when impostor syndrome creeps right back in because it’s a new challenge,” she says.

The coping strategies that follow are often counterproductive. “Procrastination or overworking are the go-to strategies.”

These behaviours are driven by automatic internal narratives: a constant pressure to stay busy or visible, the belief that slowing down means falling behind, that competence should look effortless, or that mistakes will expose a lack of readiness.

Because these narratives tend to operate in the background, they are rarely recognised in the moment, yet they shape behaviour and push people towards overworking, avoidance or excessive checking, ultimately undermining performance.

When tasks are eventually completed, success is often attributed to overworking or luck rather than ability, reinforcing the same pattern and allowing the cycle to repeat.

The high achiever paradigm

Underneath that behaviour is a long-learned pattern.

“Lawyers are high achievers. They’re used to being the best at school, best at university, places where they receive a lot of reinforcement, praise and recognition of their intelligence,” she says.

Over time, that reinforcement can become conditional.

“The nervous system learns ‘I’m only safe when I’m being better than other people.’ Now that’s hard when you work in law, because the reality is there are a lot of great people in your environment.”

What actually helps

For lawyers already operating at capacity, Sykes is wary of advice that adds yet another set of expectations. What helps most, she suggests, are small behavioural changes that reduce friction and fatigue, and promote clarity and connection.

One relatively easy change is to take steps to lower cognitive load. Decisions that repeat every day - what to wear, what to eat, when to exercise - quietly drain energy. She advises clients to simplify wardrobes so outfits mix easily, meal prep and keep a fixed exercise routine, rather than relying on motivation at the end of long hours.

Beliefs about sleep can also get in the way. Some people internalise the idea that sleep is a waste of time, or compare themselves to colleagues who claim to function for four hours a night. Sykes says those assumptions often need to be challenged, particularly when people are already operating close to burnout.

Social relationships function as a protective buffer against sustained stress, she says. They are often the first casualty of expanding workloads. Occasional late nights are unavoidable, but habitual withdrawal from relationships is more problematic and reduces resilience over time.

Peak performance

For Sykes, peak performance is not about lowering standards or softening ambition. It is about alignment and helping people reach a state where performance and wellbeing reinforce each other.

“Lawyers often don’t get the benefits of reaching their full potential, despite outward signs of success. A lot of lawyers are really intelligent people who are unhappy.”

A lot of lawyers are really intelligent people who are unhappy.

When that alignment is in place, she says, the dynamic shifts.

“People enjoy coming to work for more than the money, the status, they get a bigger sense of purpose.”

“When you feel that what you’re doing is connected to who you are, your story, what you’re doing and where you came from and using that to create impact, you get a sense of peak performance, peak wellbeing, peak mood and you feel on top of the world.”

| Firm | London office since | Known for in London |

|---|---|---|

| Akin | 1997 | Restructuring, funds |

| Baker McKenzie | 1961 | Finance, capital markets, TMT |

| Davis Polk | 1972 | Leveraged finance, corporate/M&A |

| Gibson Dunn | 1979 | Private equity, arbitration, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Goodwin | 2008 | Private equity, funds, life sciences |

| Kirkland & Ellis | 1994 | Private equity, funds, restructuring |

| Latham & Watkins | 1990 | Finance, private equity, capital markets |

| McDermott Will & Schulte | 1998 | Finance, funds, healthcare |

| Milbank | 1979 | Finance, capital markets, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Paul Hastings | 1997 | Leveraged finance, structured finance, infrastructure |

| Paul Weiss | 2001 | Private equity, leveraged finance |

| Quinn Emanuel | 2008 | Litigation |

| Sidley Austin | 1974 | Leveraged finance, capital markets, corporate/M&A |

| Simpson Thacher | 1978 | Leveraged finance, private equity, funds |

| Skadden | 1988 | Finance, corporate/M&A, arbitration |

| Sullivan & Cromwell | 1972 | Corporate/M&A, restructuring, capital markets |

| Weil | 1996 | Restructuring, private equity, leverage finance |

| White & Case | 1971 | Capital markets, arbitration, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Law firm | Type | First-year salary |

|---|---|---|

| White & Case | US firm | £32,000 |

| Stephenson Harwood | International | £30,000 |

| A&O Shearman | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Charles Russell Speechlys | International | £28,000 |

| Freshfields | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills | Silver Circle | £28,000 |

| Hogan Lovells | International | £28,000 |

| Linklaters | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Mishcon de Reya | International | £28,000 |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | International | £28,000 |

All graphics reproduced with permission of Dr Catherine Sykes.

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Travers Smith | £55,000 | £60,000 | £130,000 |

| Firm | Merger year | Known for in London |

|---|---|---|

| BCLP | 2018 | Real estate, corporate/M&A, litigation |

| DLA Piper | 2005 | Corporate/M&A, real estate, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Eversheds Sutherland | 2017 | Corporate/M&A, finance |

| Hogan Lovells | 2011 | Litigation, regulation, finance |

| Mayer Brown | 2002 | Finance, capital markets, real estate |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | 2013 | Energy, resources and infrastructure, insurance, finance |

| Reed Smith | 2007 | Shipping, finance, TMT |

| Squire Patton Boggs | 2011 | Corporate/M&A, pensions, TMT |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Travers Smith | £55,000 | £60,000 | £130,000 |

Our newsletter is the best

Get the free email that keeps UK lawyers ahead on the stories that matter.

We send a short summary of the biggest legal industry and business stories you need to know about three times a week. Free to join. Unsubscribe at any time.